Food-Info.net> Food Products > Wine

Sparkling Wines

Wines containing excess carbon dioxide are called sparkling wines. They are always table wines, usually containing less than 4% sugar. They can be produced using two basic techniques, namely via a second sugar fermentation, often induced artificially, or direct carbonation, involving the addition of carbon dioxide.

Sparkling wines result when the escape of carbon dioxide from the fermenting liquid is prevented. The basic material is usually a dry white, rosé, or red table wine. Sufficient sugar is added to the basic wine to produce a pressure of about five or six atmospheres (units of pressure, each equal to 760 millimetres of mercury) following fermentation, assuming there is no loss of carbon dioxide. The size of the fermentation container may vary from 0.1 to 25,000 gallons. Bottles or tanks used for this type of fermentation must be capable of withstanding pressures as high as 10 atmospheres. Use of tanks equipped with pressure gauges allows excess pressure to be let off as needed. The special bottles used for sparkling wines are thicker than normal in order to withstand pressures in the range of seven to nine atmospheres. The neck of the bottle is shaped either for seating a crown cap or with a lip that catches a steel clamp to hold the cork in place.

The basic wine is clarified before being placed in the fermentation container. Several wines are usually blended to secure a base wine of the proper composition and flavour balance. The original alcohol content should be only 10-11.5%; the secondary fermentation will result in an increase of about 1%. The pH should be 3.3 or slightly less, with 0.7% or more total acidity calculated as tartaric acid, and the wine should have a fresh fruity flavour. No single or pronounced varietal character should predominate in the base wine, except in muscat-flavoured sparkling wines. Special care is necessary to avoid wines with any off character in odour or taste, or any trace of undesirable bacterial activity.

The clarified wine is placed in the fermentation vessel, and the requisite sugar for the fermentation, about 2.5%, is added, along with 1 to 2% of an actively growing yeast culture. The strain of yeast selected should ferment adequately in wines of 10 to 11.5% alcohol as well as under conditions of high pressure. The yeast cells should settle (agglutinate) rapidly and completely after fermentation.

The secondary fermentation is carried out at 10 to 12°C for best absorption of the carbon dioxide produced and should be completed in four to eight weeks. To save time, both tank and bottle fermentations are often conducted at temperatures of 15 to 17°C or even higher, and the secondary fermentation is frequently completed in 10 days to two weeks.

Tank Fermentation

Additional differences between tank- and bottle-fermented wines may develop after secondary fermentation. Upon completion of fermentation, tank-fermented wines are filtered to remove the yeast deposit and then bottled. The filtration operation can introduce air, sometimes leading to oxidative changes affecting colour and taste. In addition, it is difficult to accomplish the necessary filtration, removing any viable yeast cells, without reducing the level of the pressure that has been built up within the wine. Because of such difficulties, sulphur dioxide may be added to tank-fermented wines in order to prevent refermentation. While still in the tank, the wine is sweetened to the desired level by the addition of inert sugar syrup.

Bottle Fermentation

Bottle-fermented wines may also be clarified soon after fermentation. In the transfer process, the bottle-fermented wine is transferred, under pressure, to a second tank, from which it is filtered and bottled. In this case, as with tank-fermented wines, little ageing of the wine takes place in contact with the yeast, and sulphur dioxide may be added. The transfer process is widely used in the United States, Germany, and elsewhere.

In contrast, in classic bottle fermentation, or méthode champenoise ("champagne method"), the wine remains in the bottle, in contact with the yeast, for one to three years. During this period of ageing under pressure, a series of complex reactions occur, involving compounds from autolysed yeast and from the wine, resulting in a special flavour. Bottle-aged wine is rarely transferred, filtered, or rebottled because the addition of sulphur dioxide, required to prevent oxidation, would interfere with the delicate aroma so carefully developed by ageing. Aged bottle-fermented wines therefore are usually clarified in the bottle. In this process the bottles are placed neck down in special racks at a 45° angle. Each day the bottle is turned to the right and left, inducing the yeast debris within to move down the side of the bottle onto the cork. This process, riddling or remuage, may last from a few weeks to several months. When it is complete, all of the yeast is on the cork, and the bottle is gradually brought to an inverted position of 180°. Mechanical remuage in large containers is widely practiced.

In the traditional procedure, the cork is slowly pulled out, and the pressure within the bottle propels the sediment out of the bottle. In the modern procedure, to prevent undue pressure loss, the bottle temperature is lowered to 10 to 15°C. The neck of the bottle is placed in a freezing solution and frozen solid. When the crown cap, or cork, is removed and the yeast deposit is ejected, the process is called disgorging, or dégorgement. The bottle is quickly turned to an upright position. When performed properly, disgorging (which is usually mechanised), involves the loss of only 3 to 5% of the wine. The bottle is held under pressure while it is refilled.

The filling solution is a small amount of sweetening dosage, usually white wine containing 50% sugar. The amount added depends on the degree of sweetness the producer desires. Wines labelled brut, or sometimes nature (a term also applied to a still champagne), are extremely dry (very low in sugar content), usually containing 0 to 1.5% sugar; wines labelled extra dry or extra sec, or dry or sec, are sweeter, often containing 2 to 4% sugar; semi-dry or demi-sec wines may contain 5% or more sugar; and sweet or doux wines have about 8% sugar. In commercial practice, there is considerable variation in the exact degree of sweetness described by a specific term. If the dosage does not bring the contents to the desired level, more wine of a previously disgorged bottle is added. The closure, made of cork or plastic, is held in place with a wire netting.

If the wine has been aged for two or three years, the sugar in the final dosage does not ferment, as that in the original dosage did, because few viable yeast cells remain. Even in wines aged for shorter periods, skilful disgorging leaves few viable yeast cells on the sides of the neck of the bottle. Furthermore, the wine lacks oxygen to stimulate yeast growth and is lower in growth-promoting nitrogenous constituents and higher in alcohol than the original wine. The high carbon dioxide content also has a repressive effect on yeast growth. When bottle-fermented wines are fermented very rapidly and disgorged early, however, it is customary to add some sulphur dioxide with the final dosage to repress yeast growth.

In the United States, tank-fermented wines must be labelled "fermented in bulk" or "bulk-fermented". Bottle-fermented wines may be labelled "bottle-fermented", but only wines handled by the classic method may be labelled "fermented in this bottle."

Carbonation

Carbonation is a less demanding process but is used infrequently. Carbonated wines have many characteristics of fermented sparkling wines, and this simple physical process is much less expensive. The action of the second fermentation under pressure may produce especially desirable flavour by-products, however, and there is greater prestige value attached to fermented sparkling wines. In some cases, the wines used as a base for the carbonated sparkling wines may be overmature or otherwise inferior to those used for the fermented sparkling wines.

The base wine used for carbonation, like the base wine for fermented sparkling wines, must be well balanced, with no single varietal flavour predominating. Young fruity wines are preferred, and the wine should not contain any trace of off-odours. Since no secondary fermentation takes place, wines of 11.5 to 12.5% alcohol are used. The wine should be tartarate-stable, metal-stable, and brilliant, and the sulphur-dioxide content should be low. For white wines, the colour should be a light yellow.

A variety of techniques have been used for carbonation. Production of carbonation by passing the wine from one bottle to another, under carbon dioxide pressure, is now seldom employed because of its slowness. Carbonation has been produced in bottles after de-aeration, and this technique could be adapted to multibottle operations. Direct carbonation is frequently practiced with cold wine in pressure tanks, and if the stream of gas is finely divided, good carbonation is obtained. Pinpoint carbonation, spraying the wine into a pressure chamber containing carbon dioxide, may also be employed. Following the carbonation procedure, the wine is bottled under pressure. A cork or plastic or crown cap closure is applied, the label is affixed, and the wine is cased for distribution.

In many countries, there is a higher tax on fermentation-produced sparkling wines than on carbonated sparkling wines. The two types also have different labelling requirements, and the process of carbonation usually must be stated on the label.

There are a few low-level carbon dioxide wines on the market, produced either by fermentation or by carbonation. In Germany and other areas, tank-fermented wines, or "pearl" wines, of about one atmosphere pressure, are produced. In the United States, Portugal, and Switzerland, a number of wines are lightly carbonated at the time of bottling, adding piquancy.

There are a few wines in which the carbon dioxide comes not from alcoholic fermentation, but from malolactic fermentation of excess malic acid in the wine. The vinhos verdes wines of northern Portugal are examples of this type. This fermentation is sometimes responsible for undesirable gassiness in red wines.

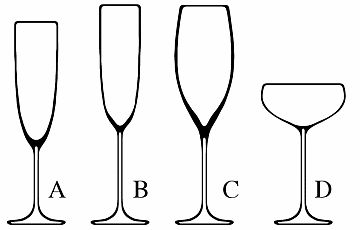

Typical shapes of glasses used for sparkling wine (Source)

Further reading :

More wine info: